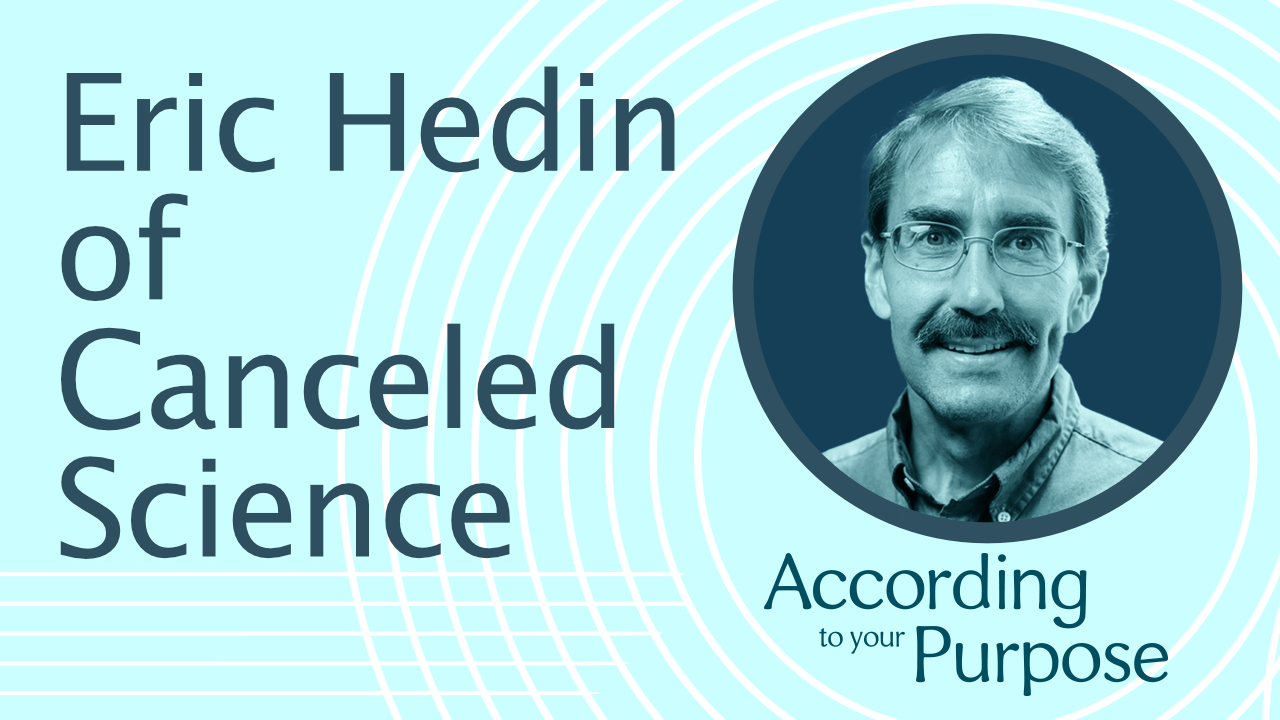

Transcript: Eric Hedin / Canceled Science - Uncovering God in Science

Eric Hedin was a physics professor at Ball State University and is the author of Canceled Science. If you're unfamiliar with Eric, he came to national prominence when Jerry Coyne, and an atheist group, tried to cancel him for a class that he was teaching about the "boundaries of science". In our conversation, we got to talk about that experience and the scientific facts that the atheist group objected to. We cover everything from the Big Bang, time travel, the science of Jesus' miracles, and even God dimensions.

[00:00:00] Taylor: On today's episode of According to your Purpose, we have Eric Hedin. He is a physics professor at Ball State University, and the author of Canceled Science. If you're unfamiliar with Eric, he came to national prominence when an atheist group tried to cancel him for a class that he was teaching about the boundaries of science.

[00:00:17] In our conversation, we got to talk about that experience and the scientific facts that the atheist group objected to. Here's my conversation with Eric.

[00:00:24] Eric, I appreciate you coming on the show. I just happened upon your book. I saw it on the Discovery Institute Press and the subject matter just interested me on a personal level. And so I checked it out. It was amazing. You're a great writer. Physics is always a little bit fun because it's almost like a sci-fi movie come to life where you can actually prove out these crazy ideas. That sounds so crazy that it can't possibly be true, but it is true.

[00:00:53] Eric: Yes. I have found that to be something very intriguing about studying science and physics over the years. It's introducing us to concepts that maybe almost seem more like science fiction than science, but it's enjoyable to learn all the aspects of our universe for that make it possible for us to live here.

[00:01:17] Taylor: For my audience who is not familiar with you, why don't we start with your, I would say, cancellation. You had an interaction with Jerry Coyne, who's a notable atheist and he had some issues with what you're teaching. I think out of insecurity reasons, because what you're teaching is pretty compelling stuff. So why don't you walk me through, I guess let's start with maybe your interest in physics, how you got, getting into teaching and then the creation of your course and leading to your interaction with is it freedom from religion? Is that the organization freedom from religion?

[00:01:59] Eric: Yes. The atheistic organization that presented a complaint against Ball State University from my class called The Boundaries of Science. That organization was called the Freedom From Religion Foundation.

[00:02:15] Taylor: So why don't we start with you getting interested in physics and then your teaching and then leading to your course.

[00:02:23] Eric: All right. Thank you. It's I guess always fun to talk a little bit about why one does the interesting things one gets to do. And my story probably just begins with a lifelong interest in nature and a love for nature. I grew up doing a lot of hiking and camping in the Pacific Northwest. Was fascinated looking at the stars as well as nature itself mountains and all that we could see the ocean rivers, trees everything that grew. So for me as a young person, going into physics as a study, a field of study for my major in college was kind of a - it was just a, almost a default decision. I didn't even consider any other major. And so I loved studying about how things were about the forces of nature, atoms matter, and applications to astrophysics. I took astrophysics course, even as an undergrad and then learning about quantum mechanics and electricity and magnetism and electrodynamics in grad school. Went to the university of Washington where I ended up pursuing a PhD in plasma physics and nuclear fusion energy, which is still on the table as a hopeful new energy source that will maybe become available within our lifetimes. But so I was working in the experimental realm and completed a post doc sort of a guest researcher position after my doctorate in Stockholm, Sweden at the Royal Institute of technology. And that was again in fusion energy research.

[00:04:23] And while I was there I began to feel like maybe I would like to shift a little bit and focus more on teaching. By that time I, I had a sense I was in my late twenties, early thirties, and I began to sense that for a lasting impact I could do better than just working with computers and experimental devices, but that it would be more significant to invest in, in people. And that people are, in my belief in God, the only thing that really are eternal around us. And so I shifted into teaching and applied for teaching positions and ended up in Indiana. When I grew up in Washington state, Indiana seemed like a very long ways away , and yet it's been my home now for over 30 years or about 30 years.

[00:05:31] And so I ended up teaching at Ball State University and it's a State university in north central Indiana. And I taught for the physics and astronomy department there a total of 15 years. I can just go on and describe a little bit about how I developed this course called The Boundaries of Science that led to the eventual controversy if that's what you would like me to get into.

[00:06:05] Okay. It started when I first came to Ball State. The department offered a number of astronomy courses just as a gen-ed science course. It was very popular. There were multiple sections. And so I was assigned to teach introductory astronomy, which I loved to do. And there were large classes, about a hundred students in each class and I taught one or two courses of that per semester.

[00:06:38] And early on I felt like I really wanted to try to build a connection with these students. Most students taking these courses were not science majors. They were in a sense required to take a course like this, just to fulfill a science requirement and they maybe majored in English or journalism or criminal justice or anything like that, but not really hard sciences. And so for them, it might not have been their first love. And I realized that, and as a physics professor, I wanted to try to connect with them a bit. And so I would ask open-ended questions. One of them was motivated by the introduction to the astronomy book we were teaching out of in the department at that time. And it said something like astronomy can help us understand the meaning of our existence. So I thought that's an interesting pretty broad statement that anyone could maybe chime in on. And so I would ask the students get out a piece of paper and write down what you think the meaning of our existence is. And then I would collect these papers, take 'em to the local coffee shop after class, and read through their responses and categorize them according to the type of response. And it was just fascinating.

[00:07:56] One of my favorite past times was to review what students were saying along these lines. And there were a number of responses that indicated that students believe that there was more to life than just existing. Probably the most prevalent category even of students at this state university had to do with some meaning of our existence related to faith in God. And then there were others that were not so spiritual in any sense and would just say the meaning of our existence is to live and then die. Some said I've never even thought of what the meaning of my existence is. And I thought, that maybe isn't the best way to go through life and a little bit tragic to just get all the way to college and never having had a thought about what the meaning or purpose of life is. So with this, and then another set of questions that I would ask, I developed a lot of data. I had well over a thousand responses in different categories. And it led me to think about developing a course where students could discuss a question like the meaning of our existence, whether there is any significance to human existence and also to understand reality.

[00:09:29] I found that nonscience majors in particular, weren't always very clear about what nature could do and what nature. Couldn't do. And that came out in a question I would ask what are the kind of limitations of science and can science explain everything or maybe are there things that science cannot explain and you'd get the typical kind of humorous responses like science will never explain true love or science can't explain my girlfriend or something like that. But a lot of students would express a faith in science that maybe was a little unwarranted, perhaps. But they would say we may not be able to give a scientific explanation for everything yet, but given the track record of science, we will get to that point. And others said, no, there's definite boundaries.

[00:10:34] So I developed this course called the boundaries of science. And our department chair at that time in the physics and astronomy department said this would be a perfect course for the honors college as a symposium in the physical sciences where it eventually was approved to be taught. And I taught it there for six years and it was a discussion based course.

[00:10:58] I typically would write questions on the board and let the students respond and then we'd get back together in groups and share answers and talk about, why is there something rather than nothing or can nature produce anything? And what about this evidence or that evidence from science? And so I tried to fill the teaching content of the course with science, from astronomy, cosmology biology and little bit of mathematics and so on physics, but the essence of the course that the students enjoyed the most was coming to the discussion time and being able to interact with their peers about what are the implications of scientific discoveries.

[00:11:54] And a lot of those dealt with this question that I mentioned at the start, namely, what are the implications? What are the implications of science for the meaning of our existence? I really wanted the course to try to leave students with the sense that we are more than just a random collection of atoms that happens to be conscious. I wanted students to come away from the course with the idea that yes, there is a purpose for our lives. And and even that there's perhaps more to the universe than just What we would describe as naturalism which is if you're not familiar with that term, naturalism is just the idea that the forces of nature acting on matter is all that there is there's just matter and energy and the laws of physics and that's it.

[00:12:53] And that the universe is all there is. There's nothing more meaning there's no spiritual realm, no heaven, no existence beyond death, no real identity of any person, just bunch of atoms interacting, according to Maxwell's equations, the laws of electrodynamics.

[00:13:25] So obviously I don't believe that's all there is to nature and I felt like the evidence from science actually confirmed that. So anyway, that's how the course came about a little bit about this course. I started teaching it in probably 2007 and fast forward, six years later, I'd been teaching it every year. It was a popular course at Ball State. And in 2013, I get this email forwarded to me from my department chair, who had received a complaint from Jerry Coyne, this evolutionary biologist, atheistic blogger and activist who has made it his pastime to try to eliminate courses like mine from the public square. And why? Simply because I didn't tow the line to naturalism. I didn't hammer on the idea that we are just insignificant specs of dust in a vast universe. Instead I suggested from looking at the laws of nature, that there's something more.

[00:14:49] Once Jerry Coyne complained, then it was picked up by the media and The Freedom From Religion Foundation threatened to sue the university claiming I had been violating the first amendment by teaching this course. And so the university in the fall of 2013, decided to cancel the course, but fortunately, and I'm grateful that I was able to keep my job and eventually was promoted the next year and then year after that, or so even received tenure at Ball State where I taught for another few years beyond that. And it's just unfortunate that there was an attack upon what I consider to be academic freedom. Within the context of a university, even unpopular ideas are meant to be tolerated - are in the sense that the university is supposed to be a place where one can discuss ideas that are maybe not the majority vote idea, as long as you're not departing radically from the requirements of the course or trying to teach a completely different topic than what you're assigned and so on. It's simply allowing students to explore the implications of scientific evidence and consider whether or not it points to something besides naturalism.

[00:16:31] Taylor: Reading through your book, it's obvious to me that you're not proselytizing or preaching or pushing any agenda. You're a true scientist at heart. You're talking about evidence. You're saying this is where the facts point us. We can talk about the implications of that, but that's where it leaves us. But it seems to me that these groups like The Freedom From Religion Foundation, it's anti-scientific to leave evidence off the table because it points to an idea that you don't like or if it points to something you don't like, then you can't consider the evidence. Much like I guess the beginning of the Big Bang discovery, people didn't like that because it undermines some of their core principles about the way they see the world which is fascinating.

[00:17:24] Eric: So I guess the course getting canceled leads to your book, Canceled Science, where you talk about all of the things that the atheist groups don't want you to know about physics, which was a fun pitch for the book. And it was a really fascinating book.

[00:17:41] So I guess to start, you talk a lot about fine tuning. The universe is fine tuned for us. What does that mean? I have a quote here. You said it's a fine tuning showcase. So you had listed all of these things. So I guess walk me through how we know, based off of science and physics, that the universe Is fine tuned for human life.

[00:18:07] Okay. Now a really complete answer to that question would take a whole semester's course of teaching, honestly. There's so many topics. I just finished an entire book detailing what we might call anthropocentric or human centered design of the entire universe. There are books that detail the design of planet earth to support life in the environment of Earth in its solar system.

[00:18:42] And then there's other books that focus more on large scale universal design parameters having to do with the fundamental laws of nature. The values of the forces that even allow stars to exist or you can go back even further and more fundamentally to fine tuning that allows the universe to exist at all.

[00:19:11] So here we go. The idea is that fine tuning is seen in that we can examine what is and determine that if the values of the forces of nature were in many cases, just very slightly different than the way they are, that something would go off course in that we would not even be able to exist. It turns out that a lot of the laws of physics and the fine tuning everything from universe to galaxy, to star system, to earth and so on culminates in humans. And we may be at the very pinnacle of the fine tuning mountain. And so that our existence is most precariously balanced on the precursor, fine tunings that exist not only currently, but all the way back to the beginning of the universe.

[00:20:24] And some have said that our existence is dependent upon the conditions that existed just even seconds after the beginning of the universe. And that is where we would see the interactions between particles that led to the certain ratios of the lighter elements that eventually led to the formation of stars that were stable, that eventually led to the process and nucleosynthesis that brings us the heavier elements that are essential for life, such as carbon and oxygen and everything up to iron.

[00:21:05] And then there's even more in a sense, fine tuning that occurs when supernova explosions occur in the most massive stars, without which, by the way we wouldn't be here. And, let me just mention this stars have a life cycle and our lives are dependent on that life cycle in many different ways.

[00:21:35] Taylor: So why don't we take a step back? Let's talk about the big bang, what it is first, and then we can talk about the expansion of space, so let's start with big, the big bang, and you can just gimme like a brief overview of what that even means. The evidence points to the earth being 13 billion years old. Is that right?

[00:22:00] Eric: The universe itself, about 13.8 billion years old and earth as a planet more four and a half billion years old. So it came not in the moment of creation, but a time later.

[00:22:17] Taylor: Okay. Okay.

[00:22:18] Eric: But yeah the big bang model is just the name that has stuck with this set of scientific discoveries that probably began with Albert Einstein back in 1916 or so he developed his general Theory of Relativity, which is one of the most accurately verified theories of science that we have.

[00:22:49] And one of the implications of that theory was that space itself would have to be dynamic, meaning actually expanding or contracting, but the evidence points to an expansion of space. And that was phenomenal because before Einstein's prediction of this philosophers, even scientists assumed that space and the universe was static.

[00:23:20] Meaning unchanging. Just had always existed. Now, if you think about it, if the universe is expanding it's getting bigger as time goes on. Is there any evidence for that? It turns out yes. About 13 years after Einstein's theory of general relativity, we fast forward to 1929 in Edwin Hubble. Using one of the larger telescopes available at that time.

[00:23:52] Just up from Los Angeles, there's a observatory and Hubble was using this a hundred inch telescope there. And he was looking at distant galaxies and finding that the further EG galaxy is from earth. The faster it's moving away from us. This has become known as Hubble's Law. And this observational evidence confirmed Einstein's theoretical predictions that the universe would be expanding because if galaxies are moving apart, that's an expansion of space and it's due to this expansion of space and.

[00:24:38] I guess becomes a theory for the origin of the universe, because if you let time run backwards, just rewind the clock. And we would see the universe contracting and getting smaller and smaller as time goes farther and farther back. Cuz if it's expanding into the future, it's contracting in the past.

[00:25:00] How small can it get only down to zero size and it's possible to actually calculate how far back in time it would be when the universe really was it zero size. That's that 13.8 billion years ago.

[00:25:19] Taylor: What are the implications of the big bang as a theory?

[00:25:25] Eric: Okay. That's a really important question.

[00:25:29] If we have a universe that began, then there must be a cause or some reason for it to come into existence. One of the implications of Einstein's Theory of Relativity is that if you rewind the tape and look at the past, when the universe began, it was not just an explosion of matter into empty space.

[00:26:01] It was a beginning of space and it was a beginning of time. These are really complicated implications of Einstein's general theory of relativity. That space and time are actually linked together and also. When the universe came into existence. This moment, we called the big bank, 13.8 billion years ago.

[00:26:29] It was really a coming into existence out of nothing. And I don't mean the nothing of empty space. It's the nothing of nothing. It is absolute nothing. There was no time before the big bang, no space before the big bang. So the cause of this, the implication is that there must have been a cause you can't get something out of nothing. Absolute nothing. We're not talking about quantum foam or some empty space or the vacuum or the laws of physics we're talking about before all that. When there was really nothing. You can't get something out of nothing in a physical sense, but a spiritual being a being like God could take nothing and transform it into something.

[00:27:35] And so the evidence of the big bang is consistent with the idea of a divine creator, who was the preexistent first cause - if you will. And that being could then volitionally decide to begin the universe and could then decide on the parameters of the universe to be just so that would eventually allow it to develop to the point where there's stars, there's planets, and then further fine tune the conditions of earth and then make it ready for life and then begin to create life upon it. So the big bang actually points towards a creator.

[00:28:28] Taylor: How do they get around the idea of God, if something is being created of nothing?

[00:28:33] Eric: Okay. That is really a pertinent question for the discussion. And there are a couple of attempts that people will use who don't want to conclude that there's a God.

[00:28:49] One of the attempts is basically a misunderstanding or a false definition of nothing. For example, Steven Hawking in the, famous physicist, much more brilliant in physics than I am. Nonetheless made a philosophical error in suggesting that. It's the law of gravity that actually brought about the universe into existence. However, the philosophical era with that is that gravity doesn't exist unless there's matter or energy or even space, and yet matter energy space, all are what we're talking about. Those are the things that need to be brought into existence. So you can't bring matter energy and space into existence by referring to something that depends on matter energy and space. The law of gravity depends on these things. So that's one attempt. Usually it's an attempt to, like I say, get around the idea of it being nothing.

[00:30:08] Or instead of a preexistent first cause that we would call God, some people try to opt for a preexisting physical state. They can't get around the idea that our universe came into existence out of nothing, but they'll say it came into existence out of a preexisting set of universes, kind of a -

[00:30:35] Taylor: The multiverse?

[00:30:37] Eric: A multiverse . Yeah. I'm sure you've heard of that.

[00:30:40] Taylor: It's such a popular idea right now and it - I don't know anything about physics but it seems to me like a - it's like a silly idea. I guess it's not silly in the sense that I guess there could be multiverse but it's still rings... It doesn't solve the problem for me. It could solve the problem of life, potentially. But it's there's still these universes that exist in infinite capacity. But it's like what created the universes?

[00:31:13] Eric: Yes, exactly. Dr. Strange and the latest Marvel movie not withstanding, this multiverse idea is completely without any scientific observational evidence. And most scientists would assert that it will forever be without any scientific validation in terms of observational evidence.

[00:31:41] Taylor: Is it is there a theoretical reason that people believe this or is it purely like a philosophical kind of wishful thinking to solve their problem of not being able to prove, to understand why the universe came into existence?

[00:31:57] Eric: I think that latter the solving a philosophical kind of dislike for the idea of a divine being is one reason that some have tried to emphasize the multiverse option, but there are some theories of physics that might suggest that there exists such a thing as a multiverse. These are unproven theories of physics such as string theory.

[00:32:34] Our universe is all that is from our perspective. And so a multiverse by definition is outside of our universe. And so by definition, we cannot receive any message from a multiverse. We can't see it or detect it by definition. And so that's why I say there will never be any observational, direct evidence of the existence of a multiverse.

[00:33:07] We could maybe further develop physics theories and see if the multiverse becomes more consistent or less consistent with those theories. But that's about as much as we could really hope for. Now, even if the multiverse is somehow let's say increased in its theoretical consistency over the years, what we know about matter and energy is that it's not eternal. There's nothing in physics that suggests that atoms or even the constituents of atoms should be stable. Eternally.

[00:33:52] Taylor: Why is that important?

[00:33:55] Eric: Because if you're going to say that the multiverse has always been, and it is the kind of eternally existent thing that gave rise to our universe, then you would be saying that a physical thing always existed and is eternal.

[00:34:17] And there's even philosophical problems with an infinite set of physical things. Just like an infinite set of multiverses going back in time, infinitely far that has philosophical conundrums that are almost self contradicting to it. So the idea of God, on the other hand, as an eternally self existent being, that is God's definition.

[00:34:52] That there's - if you're talking about a God that didn't exist forever, then you're talking about something like a false god, something like a pseudo-god or a demi-god. That really is not at all part of the Judeo-Christian belief heritage. Those would be called idols or false gods. . What do people do if they don't want to accept the conclusion that the beginning of the universe points towards a creator?

[00:35:32] Maybe put some hope in physics loopholes and a number have been presented over the years, but none have really stood the test of time and come to the forefront as okay this is the explanation we can now dismiss the idea of there being a true beginning of the universe.

[00:35:53] Taylor: This is a little off topic. You had mentioned it a moment ago, the nerd in me finds this fascinating. So you had said that time began when the universe began 13 billion years ago. So that means that time before that did not exist as a concept or as a reality rather.

[00:36:17] Eric: As a reality, that's correct. It's fascinating. Isn't it that science has discovered that time had a beginning. Now that actually sounds consistent with various statements in the Bible. The Bible is I think, unique in that it actually refers to the concept before time began. You can find those words or before the ages began, something similar to that in more than one place in the Bible. And it refers to God existing and acting before time began.

[00:37:01] Taylor: The way it was explained to me was that like our perception of time is if there was a rope, we could stand on the rope, but we could only look in one direction. We could only walk in one direction, but God can see the entire string. Is that a fair description of how it would work?

[00:37:21] Eric: Yes. I think that's a good description. Now, a rope implies a one dimensional progression of time and that's our experience, we're on a timeline. Some physicists have proposed, particularly Dr. Hugh Ross I'm thinking of with Reasons to Believe, has proposed that it could make sense to imagine that God has access to more than one dimension of time, which would more like a plane of time, which would enable him to have much greater many more options you might say could experience our time as going back and forth. It's not just a one way street for God. God can know the end from the beginning, for example.

[00:38:17] Taylor: So it would continue to allow the ability for people to have free will, in theory.

[00:38:24] Eric: Yes.

[00:38:25] Taylor: Is kind of the thinking. But it's all - but even in that mental framework, it's all happening at the same time. There is no beginning or end right?

[00:38:36] Eric: In God's frame of reference. Do you mean or?

[00:38:39] Taylor: Yeah. Yes. Correct.

[00:38:41] Eric: I don't think I could pretend to say how God maybe experience his time. Yeah, whether we would say he has no, there's no time with God or it's a more a richer landscape of time. I don't know that I could say of course, but I, I don't believe that there is any conflict with say God knowing the end from the beginning and our own free will. We're not pre-programmed. We do have freedom of choice and I think that that's consistent with what the scripture teaches as well.

[00:39:28] Taylor: So that would fall in line for - so time is a perception of it changes based off of gravity. Is that right?

[00:39:36] Eric: That's one way that our perception of time changes. The flow rate of time, so to speak changes based on the strength of the gravitational field that you, the timekeeper, happens to be in. The stronger the gravitational field, the slower, the local passage of time is, and this is a consequence of Einstein's general theory of relativity. And so it's a fascinating idea.

[00:40:12] Taylor: Didn't they prove it? Didn't they have somebody in a plane and they had lost like a second because there was a - and or am I totally -

[00:40:20] Eric: Well, no. You're right. These different flow rates of time predicted by Einstein's Relativity Theories have been proven and are constantly being proven. You know about these particle accelerators?

[00:40:38] Taylor: Yes.

[00:40:39] Eric: Okay. They're accelerating particles to near the speed of light and this is going to change their experience of time.

[00:40:51] This is according to Einstein's Special Theory of Relativity. The easier one that he developed in 1905, which says that depending upon how fast two observers are moving relative to one another, they will experience a different flow rate of time based on who's observing who. A fast moving particle experiences a slower rate of time in its local frame of reference. Like on its own wrist watch. Imagine a little particle with a clock. That clock is ticking slower than the clock in the lab of the scientist who is observing it. And this has been proven.

[00:41:41] The concept of gravity in time. That's a general relativistic phenomenon and that's been proven. And you mentioned flying in an airplane. Yes. You can put an atomic clock on a jet and note that the flow rate of time slows down compared to clocks on the ground.

[00:42:04] And you can put a clock in a satellite and because the satellite is further from earth, it's in a little weaker gravitational field than we are down at the surface of the earth and the passage of time in the satellite is slightly faster than it is on earth, where the gravitational field is stronger.

[00:42:28] Now, guess what these effects are constantly having to be accounted for in technology that we use every day. Imagine when was the last time you might have had to rely on your GPS system?

[00:42:46] Taylor: Oh, every day.

[00:42:48] Eric: Okay. Particularly when I lived in Southern California and taught at Biola university there, I don't even think I ever went out of my house without my phone and GPS on. It was just getting through traffic in that area.

[00:43:05] But our GPS system relies on a series of satellites. Satellites are both up above us, so they're in a weaker gravitational field that affects their flow rate of time, and that has to be compensated for in the electronics of the GPS system in order to make GPS as accurate as we want it to be. Also, satellites are moving and because they're moving quite fast, their flow rate of time is slower compared to the way it is on earth. That has to be compensated for.

[00:43:41] So without both of these relativistic effects constantly being taken into account and compensated for, our GPS systems would basically be worthless. So most people don't realize that, that this little device that we come to rely on, like you said almost every day, relies upon discoveries made by Einstein back in the early part of the 1900s. And so yes, it's proven and yes we have to take it into account.

[00:44:16] Taylor: I'll put a future scenario in front of you and tell me if I'm understanding it. So let's assume, a million years into the future, we've made a spaceship that can go the speed of light. Can you go faster than the speed light, or is that maximum? Is that what the laws of physics allow?

[00:44:32] Eric: The maximum speed limit. The speed of light in vacuum or open space is the maximum speed limit of any physical phenomenon, any physical object in the universe.

[00:44:48] Taylor: If we had a spaceship that's going near this speed of light, and let's say the trip was gonna take a million years. Presumably it would, you would arrive there instantaneously or your perception of it would be instantaneous?

[00:45:03] Eric: Not instantaneously, unless you were actually going exactly the speed of light. But if you were going, let's say 99.99% of the speed of light, there's a little simple formula in Einstein's special relativity theory that allows you to calculate what's called the time dilation. How much different the time rate is in the spaceship compared to say the observers left on earth.

[00:45:36] And depending on how close to the speed of light you are traveling, you could travel across the galaxy and back within, let's say just a few years - within your lifetime. But if you did that and you traveled to the other side of the Milky Way Galaxy and back, maybe a round trip of something like 75,000 light years, when you got back to earth, you might be only a few years older. If you were going fast enough, close enough to the speed of light, but guess what on earth about 75,000 years would've passed by and I wonder what kind of a homecoming that would be.

[00:46:24] Taylor: Yeah. Yeah.

[00:46:26] Eric: I don't think any of your friends would've have survived that to welcome you back. I might be a little dismal or fascinating, depending upon what you found.

[00:46:39] Taylor: Going off of this time travel idea. Can you tell me about the stars that we see in the galaxy? You had mentioned that most of the stars that we see you're seeing the light from their planet many years ago. Is that right?

[00:46:56] Eric: Yes. The light that we see from distance stars comes to us and shows us what those stars were like in the past. Depending upon how far away they are, the farther away they are, the further back in the past, we're seeing them. And it's simply because light, although it's the fastest moving thing we have in the universe ,still has a finite travel speed through space.

[00:47:22] So imagine a constellation like the Orion Nebula - just Orion The Hunter. Okay this is a famous constellation that you can see. It's about 1500 light years away. Now, light year is a distance it's about nine and a half trillion kilometers. And at 1500 light years away, light takes 1,500 years to get from the stars that make up the Orion constellation to earth.

[00:48:03] So when we finally see that light, which, we can look up in the night sky and see the Orion constellation, the light we're seeing left those stars 1500 years ago. So as we say, maybe let that light go through instruments and make analyses of the stars and their composition and their spectra were learning information about those stars as they were 1500 years ago.

[00:48:34] So astronomers are constantly observing the universe through a time machine and it's tuneable we can decide how far back in time we want to look the further back in time. We want to look the farther away we focus the telescope. So if we focus our telescope on a galaxy that is say 2 million light years away, which is roughly the distance to the Andromeda Galaxy, our closest neighbor big galaxy. It's called the Andromeda Galaxy. It's roughly about 2.4 million light years away.

[00:49:20] So when you look at that, you're seeing it as it was 2.4 million years ago. If you wanna, instead to look at a galaxy that's 2 billion light years away, which there's plenty of them at that distance, then we're seeing that galaxy as it was 2 billion years in the past.

[00:49:39] If you look, at the farthest, we can look. Roughly, the farthest galaxies that you can see are roughly 13 billion light years away and we're seeing them that many years into the past.

[00:49:58] Taylor: Is that how they figured out the age of the universe?

[00:50:03] Eric: Not exactly. That comes more from an analysis of Hubble's law, which is this relationship between the distance to a galaxy and how fast it's moving away from us. And by taking measurements of many galaxies, we can determine the expansion rate of the universe. how fast is it expanding? And then we know how big it is. So we just have to ask if it's this big now, and it's expanding at this rate, do a little math and we can calculate how long it took to go from zero size to current size. And that how long it took is the age of the universe, because that's how long it expanded from the beginning, the big bang as they call it, to current size.

[00:51:01] Taylor: How do you know the speed of expansion?

[00:51:03] Eric: Good question. It's a fairly straightforward measurement. Even almost a hundred years ago now, it was being used - say Edwin Hubble using the Mount Wilson observatory, as I said, just up from Los Angeles. I've been there and looked at the same telescope that he was using and he could determine how fast space was expanding by measuring the red shift of the light coming from distant galaxies. Now, red shift is a phenomenon that's well understood in physics. It happens when a source of light is moving away from you. And believe it or not, it's the same technology used by the police radar gun when they're trying to catch speeders so -

[00:51:59] Taylor: Really?

[00:52:00] Eric: Yeah, they use the red shift or the blue shift, depending on which way the car is moving, but essentially bounce a radar being off of your car and then measuring the change in wave of the reflected wave compared to the outgoing wave that they sent out of their radar gun. And the difference tells them the speed of the car.

[00:52:30] So it's the same with light coming from distant galaxies. We don't bounce light off those because it they're just way too far away, but they're already emitting light. So we just look at the light and we determine the change in wavelength of the light we receive compared to the wavelengths of the light as it would be when it was emitted that change in wavelength gives you the velocity of the galaxy, the recession of velocity, according to the Doppler formula it's called.

[00:53:06] Taylor: So that is how we measure the edge of the universe. What is outside of that edge?

[00:53:15] Eric: The edge of the universe has really maybe never been observed. This is a great concept. And I remember in my astronomy courses, it just was so frustrating for students like what's at the edge of the universe and the best answer we could give was there really is no edge.

[00:53:38] And that's so frustrating for us because everything that we've seen has an edge to it. Even if you look at the entire earth, you could say there's an edge to the surface of the earth. You're either on the earth or you're off the earth, or you could, take something more local.

[00:54:00] There's an edge to the borders of our country. You can go beyond it and you're just outside. But you're still on earth. But if you think about going outside of our universe, beyond the edge of our universe, where are you? There is no definition to outside the edge of our universe. You would have to actually be going into a higher dimension, a physical dimension beyond the three that we currently experience.

[00:54:34] And we are three dimensional being, and we're confined to three dimensional space. We can't even perceive higher dimensions with our senses. So if we left the universe, went off the edge of the universe. We would have to leave our three dimensional existence and somehow transcend into a higher dimensional space.

[00:54:56] Taylor: My only knowledge of dimensions comes from Interstellar. What exactly is a dimension? When you say we can't perceive it. Obviously, that seems to be true, but I don't even understand what it is. So you like explain the idea of what a dimension even is.

[00:55:13] Eric: Sure. I think it's easiest to start with lower dimensions rather than higher dimensions.

[00:55:19] So mathematics tells us that a one dimensional object is a line just it has, you can either, consider it like the X axis or a number line. You're just gonna go one way or back the other way. But just one dimension, a two dimensional object is what you would get if you took that line and moved it perpendicular to itself.

[00:55:50] So then you have a plane, like a flat piece of paper is a two dimensional object, essentially. Now, if you take that two dimensional object. We say it's two dimensions because there are two directions you can go that are at right angles to each other in a piece of paper, you can go, let's just call it left and right or up and down.

[00:56:24] Like you could draw an X, Y axis on a two dimensional paper. The X axis is one dimension and the Y axis is the other dimension. There's only two that you can draw that are at right angles for each other. Now we know there's a third dimension. You can draw a Z axis. Let's say that's perpendicular to both the axis and the Y axis in the plane of the paper.

[00:56:52] But the third dimension, the Z axis isn't in the plane of the paper anymore. It's perpendicular to the plane of the paper. And it's in and out of the paper, that's the third dimension. And if you tip that piece of paper and say moved it perpendicular to itself, you would extend it into say a cube in a cube is a three dimensional object.

[00:57:22] If you look at the corners of a cube, one corner, you can go in three different directions, all of which are perpendicular to the other two. There's the X axis, the Y axis, the Z axis. They're all mutually perpendicular. So mathematically you can extend this concept as much as you want. You can imagine mathematically a fourth dimension, which is hard for us to mentally think of envisage in our minds. Mathematically, you can describe it. And this fourth direction goes off at 90 degrees to the other three.

[00:58:12] Taylor: I don't even know what that means.

[00:58:15] Eric: You might as well not try to picture that because we really can't, but that's as simple as it is. A fourth dimension would be some direction of space that is perpendicular to all three of our familiar directions in three dimensional space. And if we could move in that direction, we would disappear from this space.

[00:58:46] If I decided somehow, and I had the ability to shift myself along that fourth dimension, as soon as I moved along that fourth dimension. I would disappear from this room. I would just blink be gone.

[00:59:04] Taylor: Because you could not exist in the three?

[00:59:06] Eric: No not because of that. But if I was a being that had this ability, I would disappear from this space just because as soon as I left this three dimensional space, other three dimensional beings would not be able to perceive me any longer.

[00:59:27] Again, it's easier if you go down some dimensions and there's this famous book called Flat Land that describes this. It's an old book describes a flat land, a two dimensional space, and we can imagine just get a piece of paper, put it on the table and make sure it's just flat. That's a two dimensional space basically.

[00:59:49] And then draw some little stick figures on there. They would be two dimensional beings and in their two dimensional world, they can perceive either of those two dimensions. They can go back and forth or left and right. But they cannot perceive up or down in or out of the paper. So you could take in your hand, let's say, you've got this two dimensional space, and then you could take your hand and put it close to the two dimensional space, but above it, those creatures would be unaware of that because they can't perceive anything existing off of the paper, which would be in three dimensions.

[01:00:34] Taylor: And we know this to be truth because of math? We've proven this?

[01:00:43] Eric: The idea that they couldn't perceive off of three dimension or off of their two dimensional space is not just math, but just the rules.

[01:00:54] Taylor: Meaning that we know dimensions and a dimension outside of the three, that we know, exists? We've proven that it exists beyond that?

[01:01:04] Eric: Okay. No, that's a good question. Do we know that higher dimensions than our three spatial dimensions exist? And I would say no. There's quite a sound belief in the realm of physics that there exist higher dimensions, but I don't believe there's any solid physical evidence of it yet.

[01:01:33] Taylor: Because presumably we could not understand it cuz we're in the third dimension?

[01:01:39] Eric: We could maybe understand it. In fact, some of those high energy particle accelerators there are some theories that suggest in certain interactions between the particles, that part of the energy of say the collision between two particles in the accelerator could generate a graviton, instead of a quantum of gravity, that might actually propagate into one of the higher dimensions.

[01:02:11] And if that were the case, it would look like what's called a missing energy signature. There would be some energy in the experiment that couldn't be accounted for because it went off into a higher dimension where we can't measure it. I don't know if it's dangerous, honestly, but it hasn't been observed yet.

[01:02:32] There may be other ways of verifying the existence of higher dimensions, but as far as I am aware of none of theoretical ideas have actually led to experimental results that prove their existence yet.

[01:02:51] Taylor: In this scenario. So let's say we're at the edge of the universe, outside of the edge of the universe, there is a true nothingness that is in an, a dimension outside of our own. Does the idea of the big bang, being provable point, towards the idea of a fourth dimensional space? Because presumably the dimensions outside of our own will say, we'll call them like the God dimensions that's dimensions outside of our own, that would be needed for the creation of the universe as a whole?

[01:03:23] Eric: That's let me just say, I don't know for sure the answer to that question. I think that Einstein's general relativity theory, which is the theory that we use to describe the expansion of the universe and the properties of space and time and matter are cons - those relativistic ideas are consistent with the concept of higher dimensions of space.

[01:03:57] I don't believe that they require them, but they're consistent with them. And again, they haven't been proven as far as I am aware of with any experimental results. I think we'd have heard of it even in the popular press if they had been proven definitely. So let me just add this, and this is not so much a scientific statement as -

[01:04:26] Taylor: It can be personal.

[01:04:27] Eric: A consistency observation. I think that this discussion about higher dimensions is consistent with some of the descriptions that we read of in the Bible. For example, after Jesus resurrection, he apparently could move in and out of our three dimensional space at will in his resurrection body, he appeared in a locked room with the disciples.

[01:04:57] The door was locked. They were there. Suddenly, Jesus appears in the room, talks to him, has something to eat and then suddenly disappears. That's completely consistent with the idea of him shifting into higher dimensions. So I'm not saying that's how it happened. There may be something spiritual going on there, but it is consistent and it's not something that you read this in the Bible and you have to throw it out because that's fairy tales. It's consistent with our physics mathematical understanding of higher dimensions.

[01:05:34] Taylor: The idea of omni-presence or interacting with having a control over three dimensional space that does not exist in our three dimensional reality.

[01:05:45] Eric: Like I said, we're stuck in three dimensional space. We can't get out of it. But apparently Jesus, after his resurrection wasn't any longer confined to three dimensional space.

[01:05:58] Taylor: Interesting. That's fascinating.

[01:06:00] Eric: Yeah. I think it's fascinating.

[01:06:01] Taylor: Yeah. that is fascinating. So I'm gonna push you a little bit.

[01:06:05] I did some thinking. Some calculations. The universe is 13.8 billion years old. All of the galaxies, all of the galaxies in the world are 180 billion. So there's more galaxies, there's more Milky Ways, in the entire universe than there are people that have ever walked the earth.

[01:06:31] So we've in, in the terms of the creation of Earth and our time on Earth, we've been here for a second. Why are you convinced that this universe that has a hundred - it has more galaxies than people that have walked the earth than we've been here for a second. Why are you convinced that there's - that this universe was made for us, that this points towards purpose?

[01:07:01] Eric: That's a good question. And some people, some scientists looking at the vastness of the universe and the huge number of galaxies, like you mentioned a hundred billion to a trillion galaxies, like our Milky way, each one containing hundreds of billions of stars. That's a phenomenal size.

[01:07:30] And how can we be significant in any way? And I think that the more we study the universe, the more we see that the nature of the universe is, again, it goes back to the fine tuning of some of the fundamental forces of nature, the strength of the law of gravity, the essential expansion rate of the universe, the amount of dark energy to dark matter, to normal matter. Then the properties, even the laws of quantum mechanics and how they interact in the interiors of stars to allow star light to function. To allow stars to shine. All of that is set up just right. To allow it to work that makes it possible for us to exist.

[01:08:35] And some would say you're just saying nonsense, because if the conditions weren't right for us to exist, we wouldn't be here. So we're here. So the conditions have to be right. Because if they weren't right, we wouldn't be here. So what's the big deal. It's a non-interesting observation.

[01:09:02] Here's the big deal. Yes, the conditions have to be physically satisfactory so that we can physically exist. Carbon has to exist. Water has to exist. Stars have to exist and so on, but what is not true and what is remarkable and I think worthy of consideration is how finally tuned many of these parameters turned out to be. They're not just broadly okay for us to exist. That's maybe what we would expect, but it's a knife edge sharp.

[01:09:44] You better not vary either way by the slightest amount, kind of fine tuning for us to exist. And I think that's a little bit of a message. If you will, a message that I believe is from God that helps us to see that this universe is not just Godless. It's not just a random set of events that allowed us to come into existence.

[01:10:08] I'm not sure if I got off from your question or if that.

[01:10:12] Taylor: No, that definitely answers my question. I saw a clip of I saw a clip of Elon Musk and it was a fascinating clip. He was on, some podcast and the guy asked him if he believes in aliens and Elon Musk is a funny guy so he was like, yeah, I've looked at all the evidence and I don't see any evidence of aliens. And they're like, oh, that's sad. He was like it's way more fascinating. It's way more terrifying that we're the only people here. He was like that means something. And, I guess the way that, that you are speaking right now, that's a big - the weight of that is heavy. That you look at the scale of this thing, the creation of this entire universe, and then it, you say this was for you. This was for you to get in contact with God. And it's a big idea that I think is scary for a lot of people.

[01:11:16] Eric: Scary is perhaps the feeling one might have, if there's a sense that I don't really want to have to deal with God or I don't really want there to be any eternal purpose for my life. If I just wanna live my life for the moment and for pleasure, and without any thought for consequences, then maybe a naturalistic nihilistic view worldview is preferable.

[01:11:55] But I think that whether or not there are other civilizations, other beings out there, any, extraterrestrials or alien life. If there are, I would say that they had to have been created by a divine creator. In the same way and for the same reasons, I believe that science suggests that our lives are dependent upon what I would call intelligent design and the action of a divine creator. Because my understanding of nature of the laws of physics has shown me that the natural interactions that we can expect between atoms will not ever lead to a living cell because there's so many more ways for those atoms to interact, that will be worthless as far as life is concerned, compared to the very narrow set of interactions that would lead to a functional set of biomolecules that result in a living cell.

[01:13:17] Taylor: So let's quickly go over that. So that was part one of the things that you went over in your book that I found fascinating. I never thought about that before. The idea of like information theory. So what exactly do you mean when you say it's unlikely? Because I guess the way it was taught to me - I'm obviously a believer in God and Jesus, going through school, they would say that it's the atoms make I think it was the Miller experiment is the, you put all these primordial things together, it makes a primordial soup. Then you get proteins become a cell, and then you have this slow gradual building from a cell. Then it gets the mitochondria. The mitochondria to a multi cell, all that, sort of thing.

[01:14:08] So I guess how does your idea of information theory differ from a gradual building from like pieces of something to a small thing, to a slightly bigger thing you would say that there's too much information to build highly complex things? Is that correct?

[01:14:32] Eric: Take something that's more reasonable for us to consider. Then the extreme amount of complexity within a human cell or any sort of a living cell. Let's take something that we can manage. Simply say a printed newspaper. It has a certain amount of information in it. You can read the newspaper and find out what happened in town over the last week, or, world news, whether stock report a lot of information now suppose that you let nature have its way with that newspaper.

[01:15:22] And by that, maybe it gets dropped in a mud puddle and nobody picks it up and it just is there and a car drives over it and maybe it rains and then the sun comes out and dries it up and then it rains again. And the wind starts to blow. And after time, the information of that newspaper, which was there, is lost due to the action of the forces of nature.

[01:15:58] This is inevitable and it's unavoidable and it always happens. And it's describable by what we might call a generalized second law of thermodynamics. This is an extension of the law of thermodynamics that you might have learned in a first year physics course, which deals with heat and entropy and -

[01:16:23] Taylor: That's the one with disorder, right? It things lead towards more disorder.

[01:16:28] Eric: That's one way to describe it, yes. But this generalized second law thermodynamics integrates the concepts of quantum mechanics and statistical physics and is applicable to information as a quantifiable. It is possible to, for example, quantify the information content in a newspaper. And what the law tells us is that natural processes will always degrade that information content with the passage of time, never increase it.

[01:17:06] Taylor: Meaning that you can't create you. Can't the facts, not the facts. The information will never get more complex over time by chance?

[01:17:14] Eric: Well no, I mentioned a newspaper and it's been a while since I've actually subscribed to a newspaper and had it delivered to my door but, if I remember, you could open to a page and it would have the the stock market report.

[01:17:35] Can you imagine leaving the newspaper outside and letting the rain fall on it? The sunshine on it? The wind blow it? Picking it up a week later and finding updated information about the stock report.

[01:17:53] Taylor: Okay.

[01:17:54] Eric: Based on what happened with nature. It's just not gonna happen. Nobody believes that would happen. That would be absurd. It always degrades it. It turns to a pile of pulp before long you. You lose all your information.

[01:18:09] So any form of information, the the software in your computer. The files that are stored there. If you leave it plugged in and there's a bad lightning storm, and you get a big voltage surge that your surge protector didn't protect you from, you never find some great new software appearing on your computer because of the voltage surge.

[01:18:34] You don't find new videos or word documents that are like ready, made answers to your homework assignment or something. It's destruction. It's cancellation of information. It's breakdown of information. That's what nature does. If you take a living thing and it stops living the forces of nature, go to work on it and turn it back to its component parts.

[01:19:09] This is decay and it happens all the time. This is what we observe. We never observe nature, increasing the information content to go from raw ingredients, to a living thing. We constantly observe nature, taking living things that have ceased living and detain them back to essentially dirt and water.

[01:19:36] And this is what I mean by the law of information and that natural processes can decrease the information content of a system. Whether it's a newspaper or a living thing with time but never increase it. So even Darwinism, the idea that you've got a living thing and natural processes somehow change the genome of that thing so that it increases its information and it suddenly has the genetic instructions to create a new organ or a new physiological system of some kind that doesn't happen.

[01:20:25] What we see is as made famous by Michael Behe in his book Darwin Devolves is a breakdown of - it's a reducing of the information content of the genome. It's it may help survivability, but it actually restricts and constricts and limits the options of the organism for future, say, responses to environmental stresses.

[01:20:59] It limits the organism to be able to respond with adaptation to future environmental stresses because the previous environmental stress has been dealt with by cutting off and destroying part of the genome.

[01:21:17] And he has a silly example that you could relate to. Say elephants might be at risk for death because of their tusks so if a mutation happened that deprived an elephant of its tusks, it might be a tusk-less elephant, and it might not get shot by poachers, and so it survives. But it's a tusk-less elephant and it can't defend itself. And so it loses its ability to respond to other environmental stresses say whatever might happen where there's another creature that is trying to attack it.

[01:22:07] And again, my expertise is not in cell biology or anything. I've just read a lot in that field. And I think it's fairly, the basics of it are fairly straightforward to understand that what we see in nature is natural processes diminishing the information content - the complexity, the functionality, the usefulness of a system with time. Never increasing it.

[01:22:42] Taylor: Meaning that you would need some sort of outside force that would -

[01:22:46] Eric: Yeah. So how do we get here in the first. How do beings exist? How does any species of life exist? My contention based on my study of the laws of nature is that natural processes did not turn a pile of atoms, dirt, and water and whatever the warm little pond is, that has been speculated about. No natural forces could turn the raw ingredients of the warm little pond into the functional complexity of a living cell.

[01:23:21] Taylor: That makes sense.

[01:23:22] Eric: Natural forces can take a living cell and destroy it and turn it back into a soup, but not the other way around. And if you have the information stored in the DNA, then you can in fact you can use that information to create the being. To generate it. If you've got the mechanism of the cell, within which the DNA can work. It can't work on its own. So in this universe, the entire universe, the physical universe that existed before any life ever existed, that universe, even if you take all of these hundreds of billions of stars, per galaxies, and hundred billion galaxies, all of that stuff matter energy that doesn't have any life in it, has less information than the information found within a single living cell. So there's just not enough of a reservoir of information within the non-living universe to concentrate it into a living thing. Even if there were such a mechanism to make that happen.

[01:24:46] Taylor: That's fascinating.

[01:24:47] Eric: I hope I made it somewhat understandable. If you have other questions, I'd be happy to address it.

[01:24:53] Taylor: I think so. I think that answers my question. What do you make? This may not be a physics question, but what do you make about the idea of consciousness? Where do you think that comes from?

[01:25:08] Eric: That's a great question. And it's one of the hard questions even within science in general is it's like, how do we explain consciousness?

[01:25:19] And it's a hard question because there seems to be a categorical disconnect between the organ of our consciousness, our brains, which is made up of atoms and the phenomenon of consciousness, namely our ability to be aware, to have a self identity, to think about thinking. There is no consciousness that we can extract from atoms.

[01:26:00] There is no consciousness quotient in a molecule, but our brains, made up of atoms, seem to manifest a consciousness. Now, my view of this, and obviously the the science of it is nascent, it's in its infancy, but my view of it is that our consciousness is not just a physical phenomen. It's not just a, what we might call an epiphenomenon of the collection of atoms that makes up our brain. It's not some emergent property of atoms. My, and I believe that I have good basis for this conclusion, is that ou consciousness is something beyond the physical. It's a spiritual aspect of our being. If you want to just use that word and what is spirit from a physics point of view? I have no idea.

[01:27:14] I don't think anyone does , but I believe that as humans, we are endowed by our creator with a spiritual nature. We're more than a pile of atoms. I believe that if God took away our spiritual nature, we would just fall down, as a lump. So our life, if you want the breath of God within us, is what makes us alive and what gives us our consciousness, our ability to open our eyes, to look around us, to think about what we're seeing, to think about ourselves, to interact with other beings, to love, to have dreams, to decide all of that is something that comes from beyond the natural realm.

[01:28:17] And of course, I believe in agreement with the Bible that when our physical body dies, as it does after some time, that our spiritual side, that this consciousness, that we have had, our spirit nature will continue to exist. And that God has promised to clothe us again with a new body that is better than the old, and of course, that gets out of the realm of physics and into the realm of theology.

[01:28:55] But just touching on that, I'm not afraid to say that because it's consistent with what we know of nature. What we know of nature tells us that there are boundaries to science. That's why I named my class, the boundaries of science. It might be more accurately described as the limitations of naturalism.

[01:29:21] There is just so much that the laws of nature can accomplish and forming a conscious being is beyond the boundaries of science. From everything that I had seen and read and studied over a career as a physicist.

[01:29:43] Taylor: I think one of the more fascinating ideas in consciousness, at least from like a biological perspective would be that, your cells continually turn over, but yet your sense of self remains. So you're continually made and new through these processes, but you still have memories. You have cellular memory. You have all these different things. You know who you are. You know your history. You know your life.

[01:30:07] You would fall on the side of the fact that we potentially even seek God, the fact that we seek beauty, would point towards the idea of God himself. Because if we were just processes, we would not yearn for something outside of our immediate stimulus. Is that fair?

[01:30:33] Eric: Yes. I think that's fair. That's a really insightful observation. Taylor, why would humans worldwide have a spiritual nature? Whether you're talking about tribes that seem to be primitive that are just basically out of touch with the rest of the world have a spiritual side and a sort of a developed spiritual sense.

[01:31:05] Now atheists, they may say I don't have a spiritual sense. And I don't believe in God. And I dismiss those outdated ideas. I don't need them. And if they're at the same time, dismissing free will and saying that's an illusion, or maybe they're even dismissing their personhood, then it's almost a suicidal thought. It's the thought that stops thought. If you think that your thoughts are only the result of the laws of physics, then there is no meaning to our thoughts. It's an intolerable thought because it cannot be self sustaining. If you believe that your thoughts are merely the result of electromagnetic interactions between charged particles in your brain, which is essentially what we're made of, then how could we ascribe any meaning or truth or reliability or trustworthiness to any thought that we had. It would be just as meaningful as what goes on inside of a star, just a bunch of stuff, interacting according to the laws of physics. And so it's basically self defeating and completely inconsistent with every human existence in every human experience. I mean. That we have ever had.

[01:32:47] Taylor: Are you familiar with Anna Lembke? She wrote Dopamine Nation.

[01:32:51] Eric: No, I'm afraid I am not familiar with that.

[01:32:55] Taylor: She's a therapist, but she does research on dopamine as well, but it's fascinating. So the book is about like dopamine regulation and brain chemistry. It's the kind of nerdy books that I read in my free time. But one of the things that she's going through, all of the things that she does when she's helping people get over addictions of any sort from drugs to video games, to cell phones or, anything. But one of the things that she recommends, I don't know where she falls in line personally, like her personal beliefs, but she talks about bringing in the idea of God or any sort of higher purpose. I think that's the word AA uses any sort of higher purpose tends to dramatically decrease relapse.

[01:33:48] It's this weird. We have this weird desire for God that we can't seem to shake. As much as the atheist would like us to not, to be purely mechanistic, it seems to be something internal to our being that we yearn for this thing.

[01:34:07] And I think that's what excited me about your book is that I think, there was a period that it looked like, oh, we don't, we no longer need God, we have explanations. But I think in the last 20 years, we're heading back in the opposite direction. We now know so much that it's again, pointing back towards God.

[01:34:29] Eric: Oh yes. I hardly agree with that. And it has been actually very encouraging for me because I've been studying this kind of interaction between science and faith for 40 years. And over the decades, there's just been an, I would say an exponential increase in the evidence that shows consistency with the concept of God or intelligent design. And, just for example, looking at the interior of the cell and finding out how complex and interacting and, the cell has been described, not like some, what Darwin might have thought as a little spherical blob of protoplasm, but it's more like a functioning living metropolis.

[01:35:30] And actually the interior of a cell is more complicated than New York city. And so this has come about from advances in our ability to actually use technology, science to really find out what's going on and to decipher how complex things are in the different systems that allow the cell to maintain itself.

[01:36:02] Yes I believe that there's an increasing set of evidences from our study of nature, that points towards the validity of the idea of God. And of course, in my personal experience, as a believer, this is all very kind of confirming to my faith, to see the scientific evidence stack up more and more solidly behind the concept of God as a creator.

[01:36:35] But that evidence from science is secondary to what I would consider to be more the spiritual evidence for God's existence and for my relationship with God. We talked about as having a spiritual nature, a spiritual side to us, and with that, spirit can perceive spirit. And that's been my experience that as I almost subject my faith to experimental testing. Is this real?

[01:37:13] If it's real, let me push in this direction. And always finding that there is something there. That God's existence is confirmed to me. It hasn't led to an emptiness or a dead end or a brick wall. But that over the years as I've pushed, in a way, as I've persisted in seeking God, just like scripture says, I find that there's something real there. And to me, this is the greatest evidence, the scientific evidence that backs up the idea that we need a designer to explain life, for example, in the fine tuning, that's all consistent with that. And it's good and I'm expectant. And it's a support to my faith, but it is, as I said, not even the strongest evidence. The strongest evidence comes from that spirit to spirit experience. Our spirit interacting with God's spirit.

[01:38:22] Taylor: So you see God both in the evidence of the world, but also just interacting with others.

[01:38:30] Eric: Interacting with others, yes. You can even look into the eyes of a newborn infant and know that there's a person there. This is more than just a bunch of atoms that happen to come into existence.

[01:38:52] There's a spiritual side to people and as I said at the start, that's really the motivating factor for why I went into teaching rather than just pure research is that people are significant. They're made in the image of God. That perhaps by sharing through teaching and interacting in the classroom, I can encourage people.

[01:39:23] Life is hard, right? And we've all had extreme difficulties, some more poignant than others in our lives, but we need encouragement and there's a lot of voices out there that may suggest to us that we're not of value. But what the Bible teaches and if this is true, we do have value. Eternal value. And that we have a spiritual side that can be redeemed through, just what, we think of the suffering and the hardship in this world and we think, why would God allow all this? I don't know that I can answer that fully. There are good theological answers, but what really motivates me to believe in God is that he cared. He did something about it. He didn't leave us alone, but that God sent his himself through Jesus, his son, into this world. Becoming one with us, a man like us, and Jesus actually then redeemed us through what he did and dying at the cross and then got raising him again from the dead. The supernatural act. But confirming the validity of what Jesus taught. And so for me, this is a response to why and how and why could God - it's like I don't know that I have it all figured out, but I do know that God cares and that Jesus became one of us suffered for us suffered unjustly if anyone ever did. And God validated that by raising him from the dead.

[01:41:15] Now that's a supernatural act. We don't see people coming back from the dead naturally. And yet this is the eyewitness testimony and there's historical evidence. We've talked about scientific evidence. We could talk about historical evidence, as well, for the resurrection of Christ.

[01:41:41] Our faith is not blind faith, in that sense. It's faith that's based on eyewitness accounts. It's consistent with science and it's consistent with human experience. And I'd say that's a lot more evidence for faith then for the idea that naturalism presents that the laws of nature, the matter and energy that exists can self assemble into a conscious being.

[01:42:14] Taylor: Yeah. It's - I had Richard, are you familiar with the Richard Weikart?

[01:42:20] Eric: Yes. And I think that I know of his work to some degree.

[01:42:29] Taylor: I actually - I talked to him a few days ago and he's a historian of ideas and we got, we were talking a lot about Secularism and Nihilism and all this different sort of stuff. But what's interesting is that the secular worldviews throughout history have disregarded pain and they've really sought to seek pleasure at all expense. There's this fascinating little book by Paul Brand. He was this doctor who. Are you familiar with Paul Brand?

[01:43:01] Eric: Yes. Yeah.

[01:43:03] Taylor: And it's a fascinating idea. The whole, the basic idea of the book is that he was a doctor who worked in India with Mother Teresa, working with leprosy patients. And his book is called the gift of pain. And I love his analogy. Is leprosy prevents us from being able to feel pain. So you have the growth starting specifically with, the colder areas, your nose, your fingers. So you have extensive growth in these areas, but his point is that the ability to feel pain is actually a gift because without the ability to feel pain, you don't have the regulation of your body. And he uses it as like an analogy for God. And I find that it doesn't make hard times any easier, a belief in God, it brings meaning into pain. You can find God in pain because it brings contrast to the good parts in your life.

[01:44:09] I think I was listening to this podcast. I forget what podcast it was, but they had said grief when somebody dies is just it's just the price that you pay for loving them. It's it's the bill come do for love. And I think about that with pain and trying to find God and hard times is that like the hard things is really it is the price you pay for the good things, because good only exists in contrast with bad but

[01:44:42] Eric: I think that there is some greater appreciation of good when there's been the lack of it or the opposite of it and, evil or pain, but yeah, pain can be a gift as Dr. Brand mentioned. And without it, I think we'd actually hurt ourselves more seriously. And that's the experience of those who with leprosy and it's actually their lack of pain receptors that leads to damaging their tissues.

[01:45:21] Taylor: Yeah. The pursuit of pleasure. It has costs and has costs for sure.

[01:45:26] Well, Eric, we covered a lot. We covered a lot of stuff here. I loved your book. Honestly I loved your book. You're an excellent writer.

[01:45:38] Eric: Thank you.

[01:45:38] Taylor: I think sometimes with science books people can get in their own way with not making it accessible. This book was a lot of fun.

[01:45:46] Eric: I'm so glad to hear that.

[01:45:48] Taylor: Yeah. It's a whole lot of fun. The black hole stuff is - I'll tease the book that there was something I wanted to get into, but we didn't get into it. It goes through what, what would happen if you get sucked into a black hole. So that'll be my pitch for the book because it's really fascinating. It's a lot of fun.

[01:46:04] Eric: Yeah, I think I mentioned something called the spaghettification so you can read my book Canceled Science to learn more about that.

[01:46:15] Taylor: I hope you will come back on the show.

[01:46:17] Eric: Oh, thank you.

[01:46:18] Taylor: I really enjoyed this. It hits all the right parts for me with my nerd interests. I appreciate you coming on the show and I hope you'll stay in touch.

[01:46:30] Okay. Thank you very much, Taylor. It's been a real pleasure to speak with you today and thank you for the invitation.

[01:46:38] If you'd like to learn more about Eric, you can check out his videos on YouTube. He does not have a channel, but there are many different interviews that he is a part of, which are really interesting and informative.

[01:46:48] You can also check out his book, Canceled Science, which we will link in the show notes. If you enjoyed this episode, you're really gonna the book a lot. He talks about black holes and A.I. and all kinds of really fun stuff. So if you're into physics or cosmology at all, I would highly encourage you guys to go check it out. It's well written and it's a lot of fun.

[01:47:05] If you wanna support this show, you can do so by subscribing here or by going and getting our mobile app, Hope Mindfulness & Prayer, which is available in the Apple and Google Play app stores. Thanks.

According to your Purpose

According to your Purpose is a podcast for seekers who desire to live a life of intention. We search out and find the most creative and innovative voices bringing God’s truth to light, in a meaningful and honest way, and bring them to you! Whether it is a creative venture, scientific discovery, physical fitness, mental health, personal growth, or stories of purpose, commitment, connection, or truth, we are fascinated by it all and we want to share that knowledge with you!

ATYP is hosted by Taylor McMahon and produced by Hope Mindfulness and Prayer, the Christian wellness mobile app.

Share:

Christian Meditation

Made Simple